Another piece of canon advice is to have a minimum number of words to write every day. Professionals have a high number, beginning and intermediate advice usually has totals less than 1000. My current target is 500 words. This is a pretty common and made sense while commuting and pressed for time. I have more time (pandemic commute) and should increase that number. Regardless, the math works; 500 words a day are two short stories a month or a novel in six months. Without editing. Just sit consistently and pound out words, in whatever time you have.

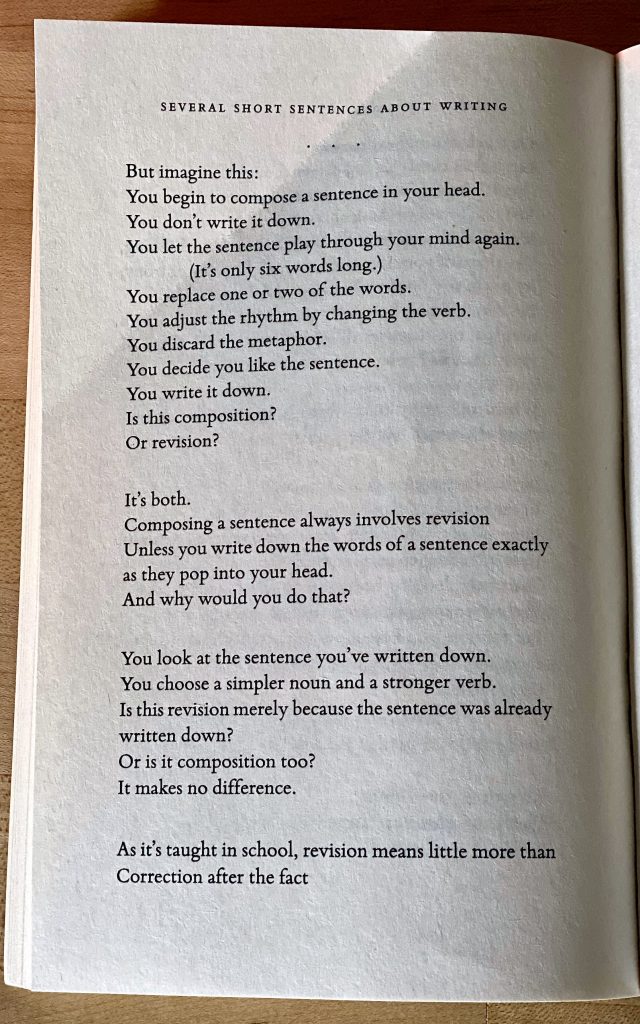

Most pro’s have a different time horizon. In the Paris Review, authors describe a habit that lasts anywhere from two to five hours every morning like Hemingway and Vonnegut. This blurb from Howey resonated:

He added (I can’t find the quote!) he usually discards the first 500-1000 words, as just warming up. Yikes. Does that mean most of my writing should never had made it past the first edit? I’ve noticed getting into a good groove requires the coffee to kick in and a few hundred words. Maybe the compromise is to increase the word goal on weekends and target 500 on school days. It’s an interesting thought…double the output 3 days a week.

The last area of conflict is how to harness creativity. I’ve read a lot on this topic; one of my many fears is twenty-five years in corporations sucked the creative juices out of me. I marvel at authors that can consistently come up with grand worlds and ideas. I’ve found that the routine helps; somewhere in between the meditation and Morning Pages, and writing consistently, creativity is more available. Story ideas flow more easily than they did a few months ago.

Canon says you have to do the work.

I call the process of doing your art ‘the work.’ It’s possible to have a job and do the work, too.”

Sit and do the work. The creativity comes from working the muscle, putting in the reps. I’ve seen it work. I’ve found creativity occurring outside of the work as well. And not just during long walks or showers. I’ll have a vivid story idea while working or driving. Or, I’ll just have a very positive, enthusiastic feeling toward the story I’m writing or piece I’m editing. And I want to work on it, right then. Sadly, I rarely have the chance. Counterpoint:

“You can’t schedule creativity.”

Reading this, I immediately have the same fantasy. I’m in a remote location, working on a piece, or multiple pieces. It’s just me, the woods and mountains, and a supply of paper, a laptop, coffee and shitty cell service. What could I do? Could I be more responsive to the whims of creative moments? And edit and whatever, all day long? The key is to be bored; a condition I never experience.

So what is the best way to reconcile conflicting advice? Throw up on the page, or write carefully the first time? Edit as you go, or wait until you finished? Small chunks of writing work, or long, multi-hour sessions? Schedule creativity and work like a muscle, or is it impossible to schedule? When the web was new, I spent a lot of time researching the best way to do things. Lose weight, eat healthy, raise kids, manage finances, etc. No shortage of best practices and success stories on these topics (multiply this by two with emergence of podcasts over the last eight years). When I’m lazy or close-minded or in a rush, I just look for answers. Don’t explain how mitochondria work, just tell me the routine to follow. But I’ve learned that best practices, methods, diets, rules only need to work for one person. We are all so different, in our biologies, backgrounds, situations and places in life, priorities and abilities, no advice or routine is one-size-fits-all. Unfortunately, the individual needs to do the work. Read all the advice and see what makes sense. Make the changes, especially if they are “low cost” (trying meditation on your own in the morning only costs time and effort). If these methods don’t work, shuffle the deck. Just because one method works for a famous podcaster doesn’t mean it will work for you.

I’ll shake things up. I will read the previous day’s writing and make minor edits. I will push the daily writing goal out to 750 on the 2-3 days that I can. I’ll schedule 2 editing sessions a week, with enough time to sink into the task. Make time for non-fiction reading. And re-evaluate, again.