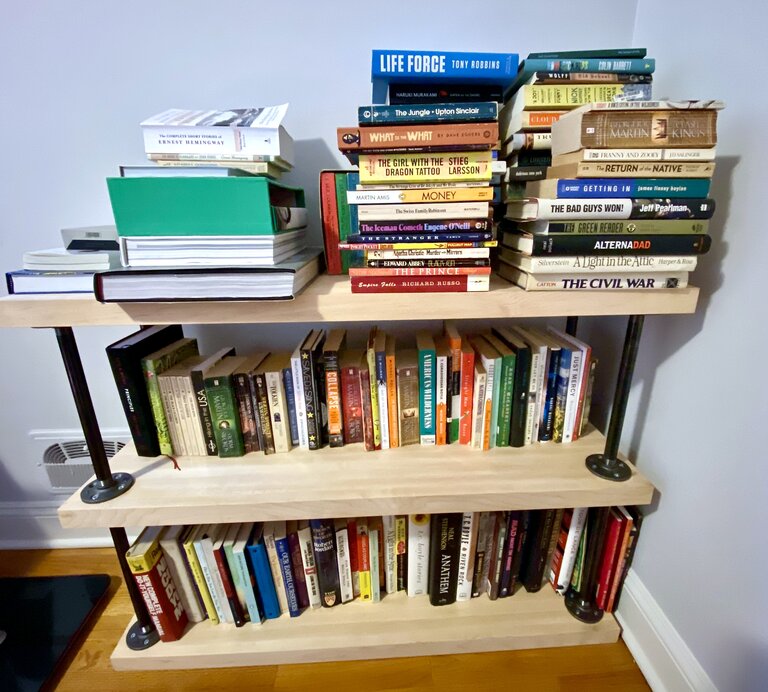

I’ve always been a reader. It’s in the genes; my mother is a tremendous reader, and I grew up around piles of books (from the EB Library, of course). Reading was always fun; only in high school and college did reading temporarily feel like a burden.

I had collections of books from elementary school I re-read repeatedly (a habit I got out of as an adult). The earliest series I remember was Encyclopedia Brown. I wanted to be a detective (based on my love of Sherlock Holmes stories) and followed the boy detective from Idaville. The concept was brilliant; each book had five chapters, and each chapter was a mystery. And they presented the solution on the last pages. Even though I fancied myself a detective in the making, I don’t remember solving any of the cases in real time. In my defense, most of the “evidence” that Leroy Brown (Encyclopedia’s real name) used was incredibly circumstantial… but I loved reading them, anyway. Also, it started a theme of reading stories set in small towns decades earlier… life in small-time Idaville seemed strange, sitting in Central New Jersey in the early eighties…

Another mystery series was the McGurk Mysteries. The McGurk Detective Agency were kids from a small town with specialities. Like a heist movie, where all the thieves have their speciality… but instead of a safe-cracker or a driver, McGurk’s agency had a tree expert, a smell expert and a kid who was “brainy”. While looking up information about the series online, a few pundits point out the series was pretty much one big trope. But, as a young reader, these devices seemed fresh. I liked the idea of an agency that met in the basement of McGurk’s parents’ house, and that a bunch of kids could solve mysteries adults couldn’t. And just enough action to keep things interesting.

The other series was The Great Brain. I read them a lot… and I must have owned a few, because I remember reading a few of the books multiple times. But, unlike E.B. and McGurk, I enjoyed them less with each reading. Everything was foreign, even though the series was set in Utah in the late 1800s. Set in small town Adenville, life seemed very different. Not just the lack of technology or flush toilets or radio and television, but the customs. Children were whipped by their parents and paddled by teachers, although JD’s (John Dennis was the narrator and younger brother to the Great Brain) family used the Silent Treatment as punishment. Families visited in the evenings in parlors. But it was the principles important to kids that never landed.

Each story involved TD, aka The Great Brain, basically manipulating and swindling. One of his primary tools/weapons was the concept of not going back on someone’s word. While this is a good principle and something to strive for, it had a commandment-level hold over the kids in the town. It was frustrating to read; I’d ask myself, why wouldn’t the swindled kid just call TD out, or tell an adult, or just not honor the agreement? Another similar device was when JD caught The Great Brain scamming. As the younger brother, he should have just told his parents what The Great Brain was up to… but TD inevitably launches into a soliloquy about breaking their parent’s heart if JD told them their son was swindling. JD agreed and wouldn’t tell the parents and have to deal with his brother’s swindle. This never seemed plausible to me as a young reader and less so now.

I read other series like Choose Your Own Adventures, but none of them resonated like the aforementioned series. I re-read these often enough they left an indelible mark.