They don’t have teams waiting at the ready to respond. They don’t run table-top exercises, don’t invest in security, or IT at all. To a small shop, IT is a cost center to manage costs on and forget. And maybe get a cool app. So both technical, security-savvy reviewers carried their worldview with them. I vacillated between ignoring them and wondering if I didn’t set up the situation correctly. In the end, I added more information about the size of the firm and the limited scope of the hack (only to one app, not the entire system).

The third part of feedback was the most useful. The story, as submitted, had an open ending. I gave Megs an opportunity to save the day and left her choice open to interpretation The reviewer argued this was the most interesting part and reminiscent to how the hacker held the fate of the company in his hands. And now so did Megs. What would she do with it? He added more questions to further drive home the point, but that was the most important part.

I agreed with this assessment, and it highlights a few of my weaknesses. Not enough character thought/development/issues. While writing, I focus on the plot and what’s happening… the most interesting part to me. But, of course, readers love characters and want to see them struggle. Struggle with a problem, struggle with morality, ethics, doing the right thing, self-motivation, etc. This feedback was a great way for me to go back and add some more elements into the piece. I did and the story is stronger.

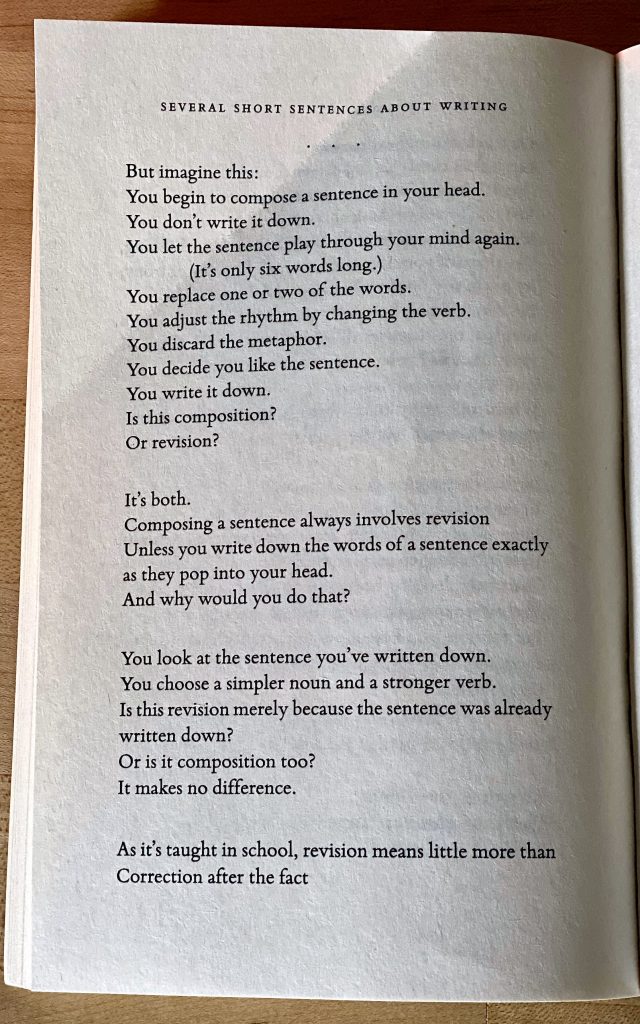

The hard part, though, is working these changes into the story, one I’ve read ten times in the last few months. My skill in editing is the simple stuff… I may not craft great sentences and prose (yet!) but I recognize problematic areas. I can make in-line edits and tweaks all day long. What I haven’t been able to do very well is integrate larger ideas or edits. These edits are a skill and something I need to work through. In order for Megs to come to this conclusion, she needs to think and express certain things early on… can’t just plop some thoughts at the end and call it a day. I tried adding a new ideas and thoughts here and there. When I read it, though, it feels just like that… “feelings” tacked on that don’t mix in well with the rest of the flow. I can’t tell if this perceived weakness true or a reaction to having read the piece so many times the additions just jump out.

In the end, even with my frustration around the technical feedback, having a writer/editor look at the piece was invaluable. The goal now is to incorporate this of feedback into my normal writing routine.

Update: I submitted this to After Dinner Conversation contest and received Honorable Mention. More on this later!