- A Second Look with my Personal English Teacher: The Stranger

Scottish Village I first read The Stranger over ten years ago, due to its inclusion on a “must-read classics” list. On first read, I found the book approachable but the plot didn’t stick with me. The ending, the style or the main themes didn’t’ stick with me.

Recently, The Stranger was mentioned on a podcast. The guest spoke at length about Camus’s prose, especially how his sentences land with precision. I decided to try the book again, but with my familiar hesitation with “literary” classics. Would I pick up the finer themes this time, or would I just scan the surface for the plot without understanding what matters? Without my junior year English teacher to guide me through, would I fully appreciate the work?So I brought in my own guide: AI, to provide critical context before I got started. I asked for why Camus’s novel matters, what themes I should notice, and what makes his style so admired.

Here’s a selection of what my virtual English teacher offered:Why Critics Find Camus’s Writing So Powerful

- Radical Simplicity as Art –Critics call Camus’s style “lucid minimalism.” The sentences are often short and direct, stripped of decoration. “Mother died today. Or maybe yesterday; I can’t be sure.” This first line is famous for its blunt honesty, almost to the point of discomfort. Camus aims for clarity without making things easy or comforting. The plain style is part of the story, and every sensory detail counts: the sun, the heat, the light. All are written plainly, but these simple details manage to feel oppressive and sacred at the same time. Thinkers like Sartre and Barthes admired how Camus left behind the flowery 19th-century style and created a new language for alienation.

- The Music of the Ordinary

- The Sun as Symbol and Structure

- Honesty as Aesthetic and Moral Force

- The Elegance of Restraint

• Read a paragraph out loud; Camus’s rhythm appears when spoken.

• Highlight every sensory reference—sun, sky, sound, temperature—and consider how those moments underline the story’s tension.

• Watch for contradictions. Where does beauty cross with brutality? That is where Camus’s clarity and cruelty meet.

• Revisit the ending when you finish. Many say the final pages are among the quiet peaks of 20th-century writing—a kind of acceptance that feels both terrifying and oddly peaceful.

Each heading above came with more detail, but this provides a good example. This framework, this grounding made a noticeable difference. I was able to see how much Camus leaves unsaid, lets meaning live in the spaces between his descriptions. With Camus, style isn’t just an ornament—it’s the story itself.

I wish I recorded my thoughts on my first read. I suspect the real impact of The Stranger goes unseen the first time, hidden in what Camus describes and what he leaves out. The real focus is Meursault’s (the POV character) reaction to everything, not the big events themselves.

I didn’t stop there. I asked my AI teacher for tips on actually enjoying Camus’s lyricism: read aloud, notice the pauses, pay attention to how short sentences string together. The cadence inside each paragraph matches the hum of daily life, while Camus varies the pace to highlight the absurd.The plot keeps things moving, and there is suspense, but the main character’s uncertainty isn’t the main event. What matters is how Meursault responds, with none of the backstory that crowd modern fiction. Camus’s realism is refreshing. Sometimes, terrible things happen and there is no elaborate explanation.

Gathering context from AI and then cycling through a conversation about themes, symbolism, and what makes the novel endure changes the experience. It fills a gap I felt reading novels since I was seventeen, and I plan to use it for every classic from now on. - The Enforced Pause: Uncommon Learning

Kinross Trail I’ve been to a few technical conferences in my non-writing career. At first, I thought the value of conferences was straightforward: exposure to new ideas, the latest trends, clever solutions, networking. Like learning in school. But the real value wasn’t in the slides or the Q&A.

It came from the enforced pause. Sitting in the audience, notebook in hand, I found my mind drifting. Not drifting away from the talk, but sideways. While the speaker worked through a problem, I thought about my specific issues. While they told stories about common challenges, I began sketching out my own solutions. I took notes on mostly of my own ideas.

Reading The Writer’s Notebook gave me a similar opportunity. I stumbled across a second-hand copy at Powell’s (published in 2009…it came with a CD). The book collects seventeen essays on exploring character, place, editing, memoir, etc. Some are full of examples from famous authors; others are more personal. But each created the same effect as those conferences: a quiet space where my mind could wander into my own work.

One of my biggest complaints about my writing process is that I don’t carve out enough uninterrupted time. Yet on a slow weekend morning, coffee in hand, I found myself reading these essays and staring into space, thinking about my stories. Sometimes I put the book down after only a few pages, not because the essay failed, but because it succeeded.

One essay in particular stopped me cold. Antonya Nelson’s “Lost in the Woods” examines the classic story structure of characters entering the woods, literal or metaphorical, searching for one thing and finding another. I nearly spilled my coffee. My current story follows two characters doing exactly that. Embarrassingly, I hadn’t recognized the lineage. I didn’t lift anything directly from Nelson, but her essay forced me to see my work inside a larger, classic framework and to lean harder into the tension between what my characters want and what they’ll discover.

That’s the uncommon value: not direct instruction, but the conditions to think more deeply. Just as a conference gives me time to reflect on work while not at work, this book gave me time to reflect on writing while not actively writing. Somewhat related to the order of things.

Now I’m searching for more books like this—essays and reflections that create space, that nudge the mind sideways into its own terrain. Serendipitous topics that don’t just teach but expand.

- Book Review: The Way

The Way Recently, I’ve read several newly released post-apocalyptic novels, including The Ancients, Annihilation, and The Way by Cary Groner. The Way good read; a page-turning blend of familiar genre elements with original twists.

The novel follows Will Collins as he travels across the American Southwest, a region devastated by pandemics and the collapse of organized society. His companions are a raven and a cat… and he can speak with both. Early in the story, we learn that Will is attempting to reach California to deliver a potential cure for the pandemic.

One of the highest compliments I can give a novel is to describe it as a page-turner. While The Way doesn’t rely on the formulaic pacing of thrillers like The Da Vinci Code, I found it difficult to put down — particularly in the early chapters. Groner’s prose is immersive, drawing the reader into Will’s world. Ironically, as the plot escalates and the stakes increase, the narrative becomes somewhat less compelling. The quieter moments are more engaging than the action-driven sequences.

Two elements, in particular, set The Way apart:

Communication with Animals

Will’s ability to speak with animals lends a surreal-ness to the story. Rather than serving as a mere gimmick, the animal companions become fully realized characters. Their presence creates a sense of companionship within the traveling group, which evolves over time to include others — each with distinct roles and skills.

Integration of Buddhism

Will’s identity as a practicing Buddhist is central to both his character and the novel’s themes. Groner integrates Buddhist philosophy throughout the story, not as background detail, but as a structural and moral framework. Will’s commitment to nonviolence becomes his defining flaw — a significant challenge when survival requires force.

Like most post-apocalyptic fiction, The Way relies on certain well-established conventions:

• Landscape of decaying infrastructure and societal ruins

• Small band of survivors traveling toward a distant goal

• “The Cure” that may save humanity

• Safe, untouched house offering respiteMinor Critiques

A few plot elements are just too convenient. The talking raven, while a fun character, provides very helpful aerial and interspecies intelligence. A young girl with expert marksmanship conveniently joins the group just as Will’s pacifism becomes a liability. At one point, the group repairs a locomotive despite lacking any relevant expertise.

The Way is a strong post-apocalyptic novel. It is thoughtful, well-written, and unique its use of classic genre elements and the unique additions of interspecies communication and Buddhism. Recommended.

- Book Review: Slow Horses

Slow Horses I watched Slow Horses when it was first released on Apple TV+. It quickly became one of my favorite streaming series. Great cast, interesting characters, and English spy craft. The series is based on Nick Herron’s series Slough House (rhymes with cow).

I heard his books described as a modern Le Carre so I avoided them… I find Le Carre slow. I could never become invested in the story or the characters. Oddly, though, I liked many of the movies or series based on Le Carre novels, such as Tinker, Tailor, Spy, and A Most Wanted Man. I tried Slough House and read along while re-watching.

Each 6-episode season is based on one book; the first season is Slow Horses. I’d read to a point, then catch up with the series. I’d never done this before; usually I’ll watch the movie or series after finishing the book.

The first 4 episodes are almost beat-by-beat from the novel. It was fun hearing the exact lines taken from the book, especially from Lamb (SH is an ensemble, but Gary Oldman as Lamb is the star). The minor changes jump out, like Ho (the techie) not wearing glasses or living in a different house. And makes me wonder why they made these slight changes.

The series drifts from the book over the last two episodes; the plot around the kidnappers is very different. They add time with the kidnappers and the victim.

This is my main criticism of the book (lesser, as Herron only spends a few pages with the kidnappers) and series; the “bad guys” aren’t interesting. The genuine conflict in SH is between the members of Slough House themselves (who treat each other delightfully horribly), Jackson Lamb vs his own team, and Slough House vs the main MI5. Any time spent away from the central characters appears an un-necessary distraction. And the main kidnapper/bad guy in the series is cartoonishly evil and unrealistic.

The show runners for the series could have handled the kidnapping in the abstract by using news reports, intel, and keeping the camera with the main characters. It felt like they didn’t trust the viewer enough.

Other aspects of reading while watching were interesting. Namely, as a reader, I didn’t have to conjure pictures of locations (the notable Slough House or the starkly contrasted MI5), how the characters looker or spoke, or even the general vibe. I would have come up with a slightly different take on River Cartwright… I would have had him more serious, while Jack Lowden plays him with a lighter touch.

Slow Horses is a good read, far better than any Le Carre I’ve ever attempted. I want to read and rewatch with the other two novels, and contrast the experience to reading one that hasn’t been turned into a season. Herron’s writing is a perfect combination of smart, literature-esque, strong characters but with a strong plot that moves. Highly recommended.

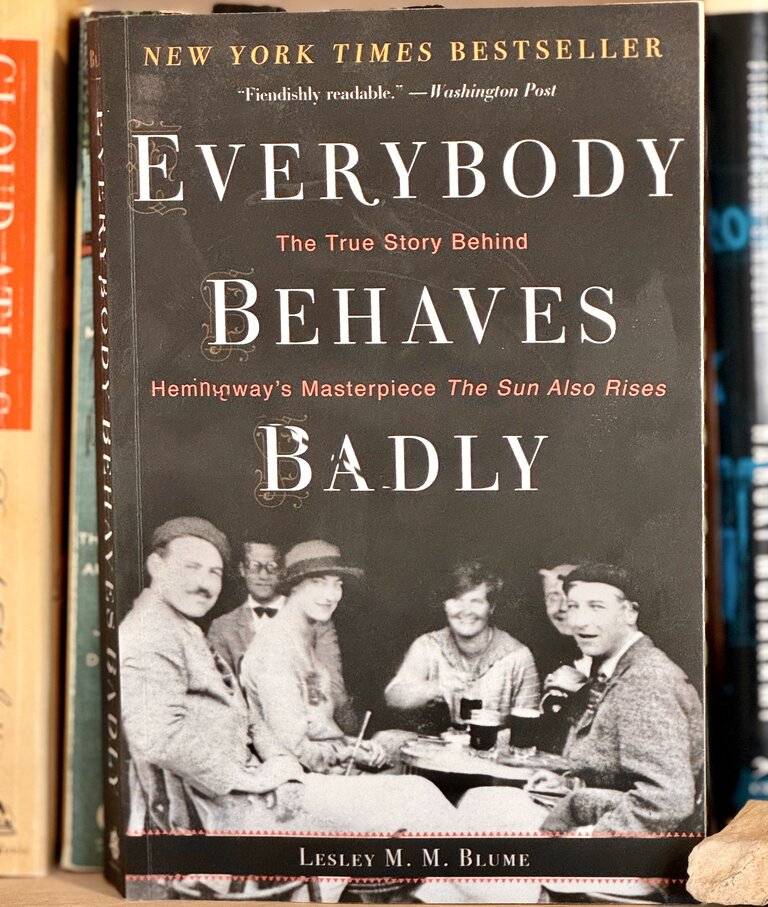

- Book Review: Everybody Behaves Badly

Behaved_Badly Readers of the blog know I am a Hemingway fan. I read The Sun Also Rises during my junior year in high school along with The Great Gatsby and Huck Finn. The Sun Also Rises was the rare book I loved upon first reading and have re-read it four or five times since high school.

Everybody Behaves Badly by Lesley M. M. Blume is the story behind The Sun Also Rises. This book was featured on One True Sentence podcast in 2020 and went into my Amazon wishlist. And there it sat until Ryan Holiday included it on his November 2023 book list. Seemed like the universe was trying to tell me something, so I picked it up… although I was still wary.

I read a similar book, The Undoing Project, which provides the backstory to the writing and authors behind Thinking Fast and Slow. Everybody Behaves Badly is a much better, more interesting read and highly recommended.

Blume tells the story of Hemingway in Paris in the 1920s, from his background as an unknown writer who schmoozed his way into the (already) famous literary scene in Paris. Here we meet so many of the people Hemingway would use as characters in The Sun Also Rises, from Robert Cohn to Lady Brett Ashley. We get enough of Hemingway’s background to understand who he was, but not an exhaustive biography.

More importantly, we get an account of Hemingway’s’ trips to Pamplona and the bullfights, especially the trip in 1924 with Harold Loeb (portrayed as Robert Cohn), Lady Duff Twysden (Lady Brett Ashley), Pat Guthrie (Mike Campbell) and Donald Stewart (Bill Gorton). The Sun Also Rises is a retelling of this trip, with the characters and events only slightly altered. One of the great revelations of Everybody Behaves Badly was how close to a straight travel story The Sun Also Rises, a beat by beat retelling of events.

This covers about 2/3 of the book. The final third describes life for Hemingway during and immediately after the publishing of The Sun Also Rises, which made him an internationally famous author (his goal). The epilogue details the lives of the characters/real friends (that word is doing a lot of work here) after the publishing. Amazing to see how much their inclusion in The Sun Also Rises affected their lives for the worse.

I tried to co-read The Sun Also Rises with Behaves… I’d read along while learning about the circumstances around the writing. A shocking thing happened, though… while I truly enjoyed Everybody Behaves Badly, The Sun Also Rises read very slow, especially to start. I’m not taking The Sun Also Rises out of my pantheon of favorite/best books… I wonder if I was just in a rush to get to the bullfights, and also to start other fiction novels stacking up on my to-read pile (an unread David Mitchell and two William Goldman books). But I couldn’t finish it… felt like Jake Barnes spent seventy pages aimlessly drinking in Paris (at the bars and restaurants Hemingway frequented, of course).

Behaves is a fun and easy read. Blume shows us where and how The Sun Also Rises events, places and characters originated. The Sun Also Rises is still one of the best novels of all time, although my journey over the last few years (reading a ton of short stories, including most of Hemingway’s) tilts me toward his short stories instead of his novels… a complete 180 as per my thoughts a few years ago.